Fazilat Soukhakian

Art

Click images for captions

Fazilat Soukhakian’s approach is an active, inquiring one. The Iranian artist-photographer’s work continually records and questions what it means to exist in our contemporary world—what it means to engage with it, to have a stake in it. Soukhakian makes images that are grounded in critical inquiry and steadfast conceptual frameworks, rooted in personal experience and observation. Her photographs are visually arresting, as disruptive as they are adaptive. “The political landscape and the social balances throughout the world keep evolving,” says Soukhakian, “which keeps me driven to tackle new issues.”

In her own words, Soukhakian is “a visual storyteller who observes, records and shares her concerns regarding social and political issues, which surround me in a pursuit for social change and justice.” Soukhakian’s personal documentary work comprises high-contrast shots, almost relics of the sites and strangers she encounters. Those encounters are dramatically composed, but in Soukhakian’s photojournalistic work, there’s something equally dramatic—not for its composition, but for the way it so captures the realness of the world, the tension, tragedy, joy, spectacle. Much of her portfolio depicts such expressions of national identity and citizenship: the D.C. Fourth of July celebrations; various processions of officials, soldiers and worldwide summits; the flags, faces, banners and raised fists of a pro-Palestine rally.

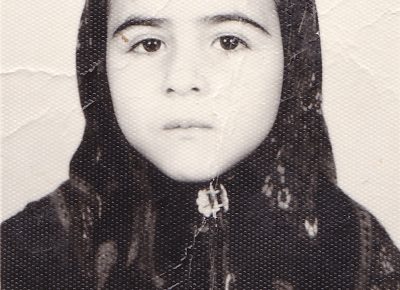

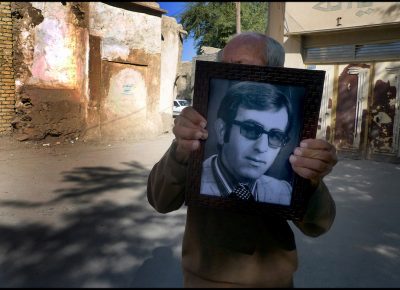

Soukhakian’s artistic practice compels with a more intimate lens, constructing pictures that investigate and upend, incorporating artistic techniques and elements that evolve to suit what each new concept demands. She examines gendered power dynamics in relationships and domestic spaces (Here… I become), and takes semi-concealed portraits of elderly Iranians—those who lived in Iran both pre- and post-revolution (This is me). A few of her projects feel especially personal, like Singularity, which brings viewers into the homes of and face-to-face with women in Iran who choose to live independently (“In my country, unmarried women who live separated from their families have to pay a price”). In Forbidden Hair, Soukhakian affixes ponytails and pigtails by nail, vividly recounting a memory of her third-grade teacher excoriating a young Soukhakian for not covering her hair.

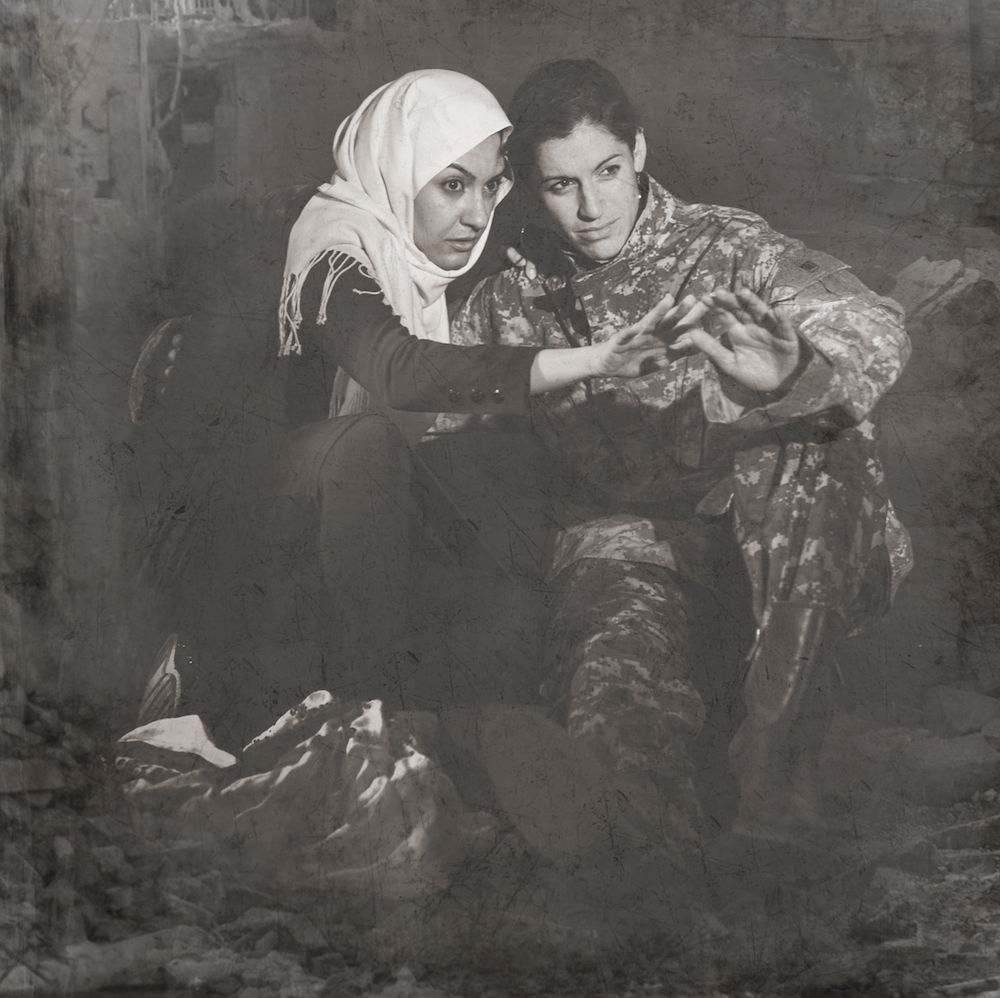

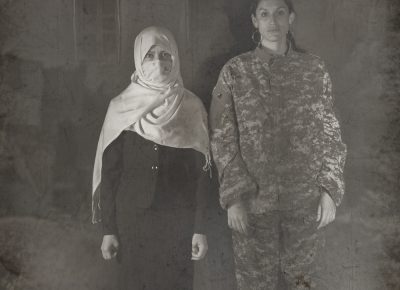

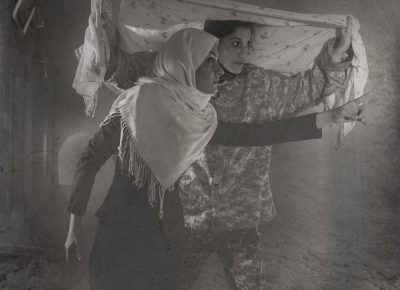

Still, other series further widen the scope, exploring the experience of violence, hard and soft revolution, and the push-and-pull of East and West. An Anonymous Battle stages shots of a model wearing the hijab and abaya in various poses: with wine glasses, a MacBook, on a motorcycle and on a longboard. The series stylizes “an ever-growing struggle between tradition and modernity throughout Islamic countries,” but also challenges the Orientalist views imposed on Muslim women by Western media. In We Share the Same Feeling, Soukhakian visualizes the shared feelings among women—those from Iran-neighboring countries who, like Soukhakian, grew up amid war, and those who are American veterans returning from war in the Middle East. “Talking to them made me realize how similar these women of war from different worlds (East and West) feel.”

Each of Soukhakian’s series intertwines with and confronts the shifting, sometimes opposing forces that Soukhakian interacts with and interrogates. Always, Soukhakian continues to observe, absorb and grow—as the world shifts and changes, so does her work evolve.

Since receiving her BFA from Tehran University and her MFA from the University of Cincinnati College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning (where she continued with PhD studies), Soukhakian was appointed Assistant Professor of Photography at Utah State University, teaching the practice, theory and history of photography. Her work has been exhibited, recognized and accoladed widely by galleries, museums and arts organizations around the world. She is currently working on two projects, “one regarding refugees, and another about the LGBTQIA community in Utah.”

To keep up to date with her work, visit soukhakian.com.

SLUG: To start, what first drew you to photography as an artform? What has kept you with this medium throughout your artistic and professional career?

Fazilat Soukhakian: Photography has always been my passion. At the age of 18, I chose photography as the major for my undergraduate studies, and I was immediately inspired by the fact that photography records the immediate reality—something Roland Barthes describes well: “a reality one can no longer touch.”

I no longer see photography merely in this perspective. Rather, it has become a medium for me to communicate with my surroundings, a way to craft stories that need to be told. The photography community in Iran, and especially in the field of documentary photography, was a tight-knit and inspiring body, composed of brave men and women who were using this medium to raise their concerns about social and political issues around them. This affected my perspectives, and I was drawn to and aligned with this quest for raising awareness to the issues that surround us. The political landscape and the social balances throughout the world keep evolving, which keeps me driven to tackle new issues.

SLUG: From examining “the role of the Muslim woman in a changing Islamic society” to documenting anti-violence demonstrations, your work takes a powerfully postcolonial and feminist approach to entrench viewers in the deeply political and deeply personal. Viewers are faced with images that confront contemporary manifestations of violence, gender, religion and much more.

I’m interested in how you create these projects with such care. What sorts of risks do you feel you need to address or overcome, if any? How do conflicting forces—internal, external, personal, social, etc.—bear in the making of your work?

Soukhakian: As an Iranian woman, born and raised in the Middle East, you would automatically be confronted with the political and social issues that surround you. I struggled and had to fight hard through every stage in my life to prove that I earn my rights and status, as an Iranian woman and more specifically as a female photographer in a patriarchal society. This struggle gave me a very specific perspective on life, professionally and personally, and proved to be a continuous influence on my work and life.

Feminist theory is not something I initially tried to actively portray or weave into my work. It rather is inherently part of my life as a Middle Eastern woman, and it naturally evolved in that direction. I lived with many other Iranian women, photographers, artists and other professionals who are more brave than me and who spoke up for the causes they believe in. They are fighters who are driven to showcase their opinion, intelligence and talent, risking their lives in the hope to raise awareness and pursue social equality and justice. They exhibit their work, which directly critiques the local forces of power, without fear of being arrested. They are the ones that are changing the course of history in Iranian society—slowly but surely.

SLUG: How do you navigate such themes when operating under the “Western gaze”?

Soukhakian: Moving to the United States, I had this image of myself and my generation of women in my mind, but was confronted with what you call “a Western gaze.” People reached out to me with sympathy, seeing me and other Middle Eastern women as helpless sheep in a patriarchal society, unable to grab hold of their rights and desperately needing external help to overcome this.

This Western perception is an image that I have been trying to break through—albeit a difficult hurdle to overcome, since it is an image that has been shaped throughout time. Iran has been going through tremendous changes, and since I no longer live there, I must acknowledge that my social and political perspectives, and my other points of view, constantly change and evolve through influences from here and abroad. There is no doubt that the Western culture has an influence on my ever-changing perspectives—and while I see the gaps in my culture more intensely, I also see problems and I have to remind myself that I need to be delicate in the way I portray my culture and people. I try to step back occasionally and look at my gaze objectively from both perspectives—and there is a middle ground where freedoms are found and strong personalities are highlighted.

SLUG: More generally, I’d love to hear your thoughts on the power of photography and the image—both in fine/contemporary art and in media/journalism—in changing ideas and challenging norms in contemporary society, as well as globalized politics.

Soukhakian: Politics have been notorious for twisting certain realities. It is important for the people, across borders, to be informed about the actions of their representatives and leaders—this keeps powers in balance. This is especially important in an intensely interconnected global community. Photography has been a powerful medium, historically, to provide this. A capture of a moment in time can ignite a passion in people to speak up and share their vision. Whether this is a supporting voice or a condemnation depends on the person and situation—but it is important that everyone has the opportunity to get the facts. The general population still believes in the power of photography to reflect the truth, beyond the tangents of the media and politics.

SLUG: I’m moved by your series, We Share the Same Feeling. In your artist statement, you note that “These staged photographs represent my vision for a better world in which we share our common feelings and protect each other, standing against a bigger enemy instead of standing against each other.” In making your work, how do you take into consideration the audience’s reactions, if at all? Do you hope that they will react in a particular way, and if so, how?

Soukhakian: This was the first project I worked on after arriving to the United States. It was quite challenging with my Iranian roots to connect with various veterans who had returned from Afghanistan and Iraq. I interviewed many of them and we spent many hours talking about their experiences and their points of view. Having spent most of my childhood during the war between Iran and Iraq, I know how horrifying and traumatizing this environment is to a person, no matter if you are a civilian or a soldier.

While the United States is a country with a universal feeling of pride and patriotism among its citizens, many of these veterans shared how war has changed them forever, how they could never be the same person again, and how they feel alienated in their own country after coming home: a result of being forced to do things which they did not want to do—yet no choice is given to a soldier in war, only an order. I witnessed how these people were struggling with secrets from the battleground, and often guilt and fear.

When I interviewed one female veteran in particular, she said something that inspired me towards the format of this project. She acknowledged that she was experiencing similar fears as the local Iraqi and Afghan women. She felt as if she knew them and felt that they also knew her, yet they were slated to be considered enemies of sorts. I had a variety of reactions to this project; many people shared that they were moved by this, especially after hearing some of these talks that the veterans shared with me. Others did not want to touch this topic, possibly to avoid confronting themselves or challenging their beliefs. It was my objective to intertwine childhood memories with experiences as a civilian in war and the emotions of a soldier in a foreign, supposedly hostile, country.

SLUG: What cameras and techniques do you use to shoot?

Soukhakian: To be honest, I do not believe that one specific camera or technique is right for me. The quality and options of photographic equipment have become so advanced that you can shoot your frames with almost any equipment. Nowadays, cell phone cameras have even become exceptionally great, and they provide another advantage for the documentary photographer: They blend into the environment—a threshold is removed, a way to overcome part of the intimidation that can be perceived by people when being photographed. That said, most of my work is digital, and I choose my equipment depending on the nature of the project that I work on. During my press photographer days, I would mostly shoot with a Canon Mark III, but now I experiment with the Nikon D810. The advancement of technology has pushed photography beyond the technical skill (it has evolved to be more accessible to the general public with an easy learning curve) and focuses now more on the story and concept behind the image.

SLUG: I’ve noticed a shift to studio shots in 2015’s An Anonymous Battle and Forbidden Hair, as opposed to the field environments of some of your earlier series. How do you feel your style has evolved?

Soukhakian: This shift was a direct result of the nature of the projects that I have recently tackled. After experimenting with some test photographs in different situations and settings, the ideas for both An Anonymous Battle and Forbidden Hair lent themselves better to a photoshoot in a studio environment. This challenged me to transition from the field, an environment which I was used to and comfortable with, to a studio environment, a rather unchartered territory for me. This framework of experimenting with new settings keeps pushing my boundaries, and keeps the inspiration going.

SLUG: I’d love to hear more about how you’ve developed your individual photographic style. Who or what sources of inspiration/influence do you look to?

Soukhakian: My mentors taught me to look at and study a hundred images per day to get inspired and learn about the international, visual culture. One of my earliest sources of inspiration was Lewis Hine, whose powerful imagery of child workers in various settings resulted in child labor laws—effectively making a difference through photography. This is when I realized the power of photography, and his work has continued to inspire me. Many other artists have inspired me throughout my career, such as Nan Goldin, Diane Arbus, Sally Mann, Stephan Van Fleteren, Abbas Attar and Bahman Jalali, among others. I still get inspired frequently when I witness work from artists that were unknown to me in the past, whether they are established artists or young, upcoming talent.

SLUG: How has living in Utah informed your artistic practice?

Soukhakian: The research component of my position as an Assistant Professor at Utah State University permits me to experiment both with photographic projects as well as research and writing. I recently finished my doctoral research, which focused on the representation of gender and sexuality in Iran through the lens of the king of Persia in the 19th century as well as contemporary Iranian photographers. This stable environment allows me to continue this type of research, which combines the artistic photography component with a theoretical understanding of that specific topic. Utah has been a very interesting place to me—it has certain intrinsic cultural similarities to my home country, and I am learning more and more about the local culture, which will lead me towards creating some related work in the future.

To keep up to date with Fazilat Soukhakian and her work, visit soukhakian.com.