True Horror: Thirteen Years of the Working Dog

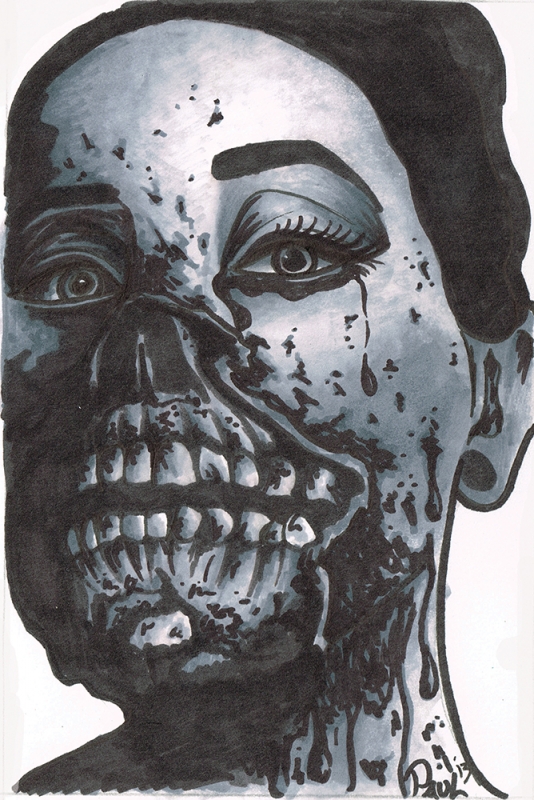

Art

Working Dog is an unofficial fixture of the University of Utah’s highly ranked graduate creative writing program. Named after the phrase “working like a dog,” the premise is simple: a once-monthly evening of art, wine and students reading material from their portfolios. Created in 2000 by then PhD student Jeff Chapman, the group has grown from a ragtag band of exhausted grad students to a funded and sanctioned extension of the graduate program.

I was first made aware of the Working Dog series by Professor Kathryn Cowles, author of Eleanor, Eleanor, not your real name. She gave extra credit to those of us who attended and wrote about the experience. My first reading was the October Scary Dog, a night whose theme contains disconcerting and jarring horror. At 19, I was mostly excited about the free booze and pretending to be an adult, but, after hearing someone recite a short story about killing a Saint Bernard and sewing himself into the carcass, I was hooked. I felt sick after the story, like Guts by Chuck Palahniuk sick, like The Exorcist sick. Andy Farnsworth is a PhD student at the U who worked with two other people, Sadie Hoagland and Raphael Dagold, during his time putting together the Working Dog. Farnsworth dissects the feel of the Scary Dog readings, saying, “They’re about murder or some sort of social infraction. It’s funny to see what people come up with and what people think is scary … It’s a good chance for people to show the theatrics behind their work.” I had never been to a legitimate poetry reading before that night (coffee shop readings don’t count), and I was quickly sold on the importance of poetic performance.

Not all of the Working Dog readings are about guts, ghosts and violence. Most of the monthly readings—held during the fall and spring semesters—are without a theme and allow students to perform 15–20 minutes of their material. Even though the group is independent of the graduate program, the U’s English department sends at least one or two delegates to each meeting to observe. The students aren’t looking for approval of the faculty or a grade at Working Dog, just the approval or condemnation of their peers, says Farnsworth, jokingly.

“Scary Dog is a rapid-fire reading [of five-minute performances] … So you’ve got folks who are like, ‘Well, I have to pick a page or section of something that may or may not be scary, but I take it out of context and no one knows what the fuck is happening,” says Meg Day, a PhD student and the 2013-15 director for Working Dog. Day feels that even though visual formats like movies have taken over as the primary media for horror, the written word of horror does not have to match the intensity of visual media to conjure feelings of true horror. “The expectations of the horror genre are mapped out in film. What makes things like the Working Dog great is it shows something broader—the space of not knowing, horror, confusion or terror. This is how much broader it can be,” says Farnsworth. “I love film—I’m not trying to talk film down—[but] there are things that work in the novel in a different way. Like, when you live with the horror in a novel, it’s for weeks—it’s not a two-hour thing. You live the headspace of this insane or depraved person, whereas with a movie, you’re in and out.”

For Farnsworth and Day, Working Dog has provided a community and an audience for their work, both as writers and performers. “I have to have the sheer threat of humiliation of reading in front of a group and making them feel uncomfortable or making myself feel uncomfortable to really know what I’m doing. I try to write on my own and I try to revise on my own and I’m terrible at it, unless I have other people there to shame me or applaud me,” says Farnsworth.

Day, who is originally from Oakland, Calif., initially felt put off by the lack of diversity in the Working Dog contributors, but has since seen both its audience and readers become much more diverse in every sense of the word. Day says that when she first came to Utah, she felt uneasy about the political culture surrounding the creative writing program. After attending her first Working Dog, however, she was greeted warmly by the community, mitigating her initial uncertainty. Day stated that Working Dog, unlike the Guest Writers Series and the City Arts Program, is a much more accessible avenue for the public to get involved in creative writing. “There aren’t a ton of venues for literary expression,” says Farnsworth. “[Working Dog] reminds me what it feels like to bond as a writer.”

You can attend Scary Dog on Oct. 24, at 7 p.m. at the Art Barn. For more information about the group, or to find a way to get involved, email wrkngdg@gmail.com or find them at facebook.com/w.orking.dogg.