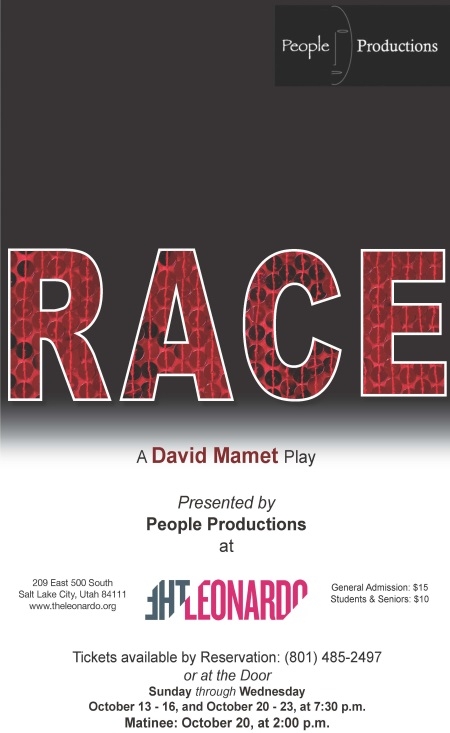

People Productions: David Mamet’s Race

Art

I walked out of last Sunday’s performance of David Mamet’s “Race” at the Leonardo with two conclusions. People Productions, which I’d never heard of before, is one of those groups that is capable of leaving me with a knot it my stomach and something real to think about. And, Mamet’s script, while problematic and manipulative, is also worth discussing, mounting and writing about.

Devoted to “celebrating African American Theatre,” People Productions, is now in its thirteenth consecutive season. The group, which had its local premiere in 2000 with James Baldwin’s “The Amen Corner,” was originally founded in the ’70s by Californian actor Edward R. Lewis. After moving to Utah, Lewis revived the moniker with collaborator Richard Scharine. With few exceptions, Scharine directed and Lewis acted, along with others, until Lewis’ death in 2009 from cancer. The group is now under the artistic direction of Yolanda Wood, a Salt Lake based performer/director who you might have seen in productions by SLAC, Plan-B or in Lawrence Kasden’s recent film “Darling Companion.”

Lewis, who was black, found Scharine, who is white, through his reputation as a co-teacher of a decades-old “Black Theater” course at the University of Utah. Though mostly retired, Scharine maintains this course, along with a class on American political theater. I asked him how he academically defined “Black Theatre,” and his answer basically coincided with much of what the company has performed. Scharine’s course starts with Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun,” because “it was the first work by a black author to play on Broadway,” thus penetrating the U.S. mainstream. Scharine also spoke at length of his admiration for black writers such as August Wilson, Pearl Cleage and Ntozake Shange, whose seminal “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When The Rainbow Was Enuf” the company has mounted twice.

People Productions’ “Race,” is an uncomfortable thriller––at once fun and painful in its excavation of the collective American fear of the eponymous subject. Scharine brought the play to the attention of the board of the company after seeing it in London last May. As reprehensible as he finds Mamet’s conservative politics, “Race” was a script he was champing at the bit to tackle. Scharine loves Mamet’s poetic, if vulgar, language and People Productions’ version of “Race” is an absorbing script executed expertly. The lines and scenography have the easy rhythm of the modern high-budget television series, carefully pared down to just three blackouts in under 85 minutes. The four characters, who at first seem utterly stock, unfold themselves rapidly and surprisingly under duress.

In its broad strokes, “Race” could as easily be a film, a novel or the ballsiest “Law and Order” script pitch ever made. A white man in late middle age seeks out a law practice made up of two male partners (one black and one white) and a junior partner who’s young, black, female and freshly graduated with an Ivy League pedigree. The client, who reeks of money and notoriety, has been accused of raping a black woman, who remains absent, anonymous and nameless for the duration of the action. The three scenes take place exclusively in the offices of Jack Lawson and Henry Brown.

At first, the play seems to be about the fate of the client Charles Strickland, who is rendered by Bill Gillane. Strickland is a hauntingly plausible caricature of white American racism, lacking totally in self-awareness and fixated with the conquest of black women, who he believes to be inherently promiscuous. Knowing a bit about Mamet––he strongly opposes affirmative action, and other programs of what he calls “brain-dead” liberalism––it’s easy to see an agenda here. He’s prodding us with a question. Will this great elephant of a man, horrible person that he is, get a fair shake in a society that prefers avoiding difficult racial discussions? The answer seems obvious to anyone who doesn’t live in a cave. Though he’s clueless and reprehensible, and though his two new lawyers at first weigh the decision to take his case like a hot potato, he’s rich enough that he’ll almost assuredly escape mostly unscathed, whether or not he committed the rape. All of their hemming and hawing about his fate and its consequences for the firm is just more absurd fodder for the momentum of the writing.

Ironically what was perhaps crafted to make us concerned for Strickland is interesting in its own right. And so our attention turns to the chilling interactions between the white lawyer, Jack Lawson, and his two black colleagues. Lawson (Stein Erikson), who never leaves the stage, spends much of his time trying to pacify his long-time partner Henry Brown. Brown (William Ferrer) resents his partner’s trust in young Susan (she’s given no surname) for taking a check from Strickland in the lobby, where Lawson has sent him to make a list of all of his racial sins. This misstep forces the firm’s hand––Brown and Lawson were still in the process of weighing the political risks and benefits of taking the case––and chaos ensues. Not fifteen minutes later, Lawson finds himself asking Susan if she’ll submit to acting out the victim’s role in a reconstruction of the opening moments of the alleged rape in court. He needs a black woman in a certain red dress to be shoved down on a mattress to prove that the absence of red sequins on the floor of the hotel room puts the case of the prosecution into question. Before the final blackout, Brown will accuse Lawson of having hired the activist Susan in a moment of blindness brought about by his own racial guilt.

In other hands, a script that forces so many extreme situations and relies so heavily on using racial tropes we all recognize might have gone horribly awry, but the work of the cast was superlative, and the production succeeds in forcing viewers to face difficult facts. Chiefly, race is still one of the sharpest tools we have at our disposal with which to hurt each other and is made palpable. What was surprising was how deeply an audience of largely white Utahns such as myself could be made to feel, through suspense and well researched acting, how vulnerable we might all be to ending up like Jack Lawson, who at the outset made the mistake of thinking that he could hold race conceptually in his head and not interact with it personally.

Look out for People Productions’ upcoming “Edward Lewis Black Theater Festival” in early 2014. This annual event, comprised of staged readings of plays the company is investigating for future performance, should be a great chance to see a broad range of plays and to introduce yourself to an important Utah institution.