Etsuko Kato: Preserving Culture and Memory through Photo

Art

When I arrive at Etsuko Kato’s home, it has just begun to rain and the air has cooled. Her 100-pound Airedale Terrier barks from inside when I ring the doorbell. Kato greets me wearing a black apron and a wide smile as she slips out her front door, remarking that her dog was meant to be about 60 to 75 pounds but surprisingly grew to be much larger.

Kato brings me through a wooden gate to her backyard, where rows of turned dirt create a grid pattern where they have just installed a new sprinkler system. Her studio space is the small back portion of their garage, walled off and without windows or plumbing. She shows me a small water heater installed underneath the long sink and explains the ways she gets around not having access to running water in the space. Rows of tools and processing chemicals are lined on shelves. She says she found most of her equipment on KSL, piece by piece.

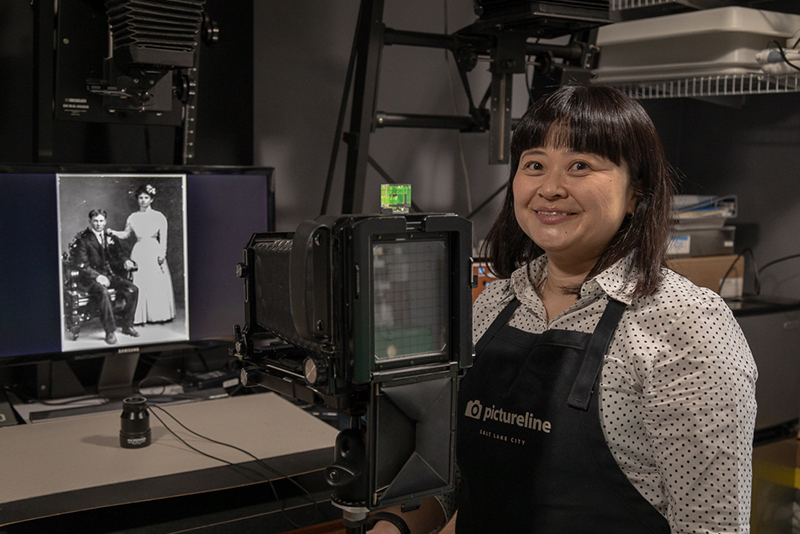

The opposite wall contains a long work table with three massive photo enlargers, two meant for black-and-white images and one for color. A back corner rack holds tiny metal and glass collodion wet plates. In the center of the room is a 4×5 Format folding camera on a tripod. She has the lens positioned toward an image of an old-timey couple on a digital screen below one of the enlargers. It is someone else’s picture that they have asked Kato to photograph, in order to preserve the image and memory in a tactile way.

“I need to know my country. I need to know my culture.”

Kato left Japan in 2002, landing in Utah and taking ESL courses at what is now Utah Valley University (then UVSC). She had planned to pursue a Master of Business Administration degree at the University of Utah, but was told her English was not strong enough. Even though Kato already held an undergraduate degree from a university in Japan, she was redirected into an undergraduate economics degree. She had done some photography in high school in Japan and decided to see how a photography for non-majors course would fit into her general fine arts requirements. She instantly fell in love and took the same course four times.

Initially feeling that business and art had no clear connection, Kato later realized that management could learn from creativity. “Business is done in a book or through experience, but sometimes it’s not that,” she says. “It’s human to human, and sometimes we need an artistic view.” She completed her degree in photography with a minor in economics.

When Kato immigrated to the United States, she was surprised at how little she felt she knew about her own Japanese history and culture. “I never thought about identity because I didn’t need to think about it,” she says. “But when I moved here, everyone asked ‘Are you Chinese? Korean?’ But when I tell them I’m Japanese, they start talking about my culture—kimono, Geisha, calligraphy. Some of these things I didn’t know about. They know more than me, even though it’s my country. I need to know my country. I need to know my culture.”

“That’s why I’m crazy about photo, because maybe I can create my own family album.”

Kato developed her current photographic practice through the determination to learn more about her culture and to preserve the memories of her family. After her former fiancé’s suicide and a college friend’s passing, Kato began taking funeral pictures of the living. Her fiancé only left one photo behind, and the 2011 tsunami in Japan wiped out all physical reminders of her friend. Because of this loss, Kato believes that we must now prepare for death by preserving loved ones while they are still alive.

“We know life and death are next to each other. Right now, I’m still alive, but maybe tomorrow, there’s a car accident, earthquake, maybe fire. Or maybe I die from darkroom chemicals,” she says, chuckling. Creating these images and helping others preserve their family history has also brought her closer to her Japanese heritage. “My family doesn’t have a family album from before World War II,” Kato says. “They were living in Tokyo and when the bomb dropped and it burned up everything. I just know their story, that’s all. That’s why I’m crazy about photo, because maybe I can create my own family album.”

Kato’s desire to preserve history and memory informs a more politically urgent purpose as well. Returning to the 2011 tsunami, Kato believes that humans have to document and learn from their past: “The tsunami had hit the same area about 100 years ago, and we lost so many lives and houses,” she says. “When I was standing in that tsunami disaster area, I only could tremble with fear—I knew of our stupidity and how small we were.” Ultimately moving towards a mindset of change, Kato says that “I think that disaster was a commandment for mankind. It is something we must remember and should never forget.” Her photography serves as a crucial element of this remembrance. In her Blue Journals series, grainy photographs are starkly stained with blue ink as a means of taking Kato’s negative thoughts and turning them into more positive, productive art.

“I want to use this paper for photographs because I’m printing my identities, making my work more strong.”

Kato is currently in the process of transitioning her collodion practice from metal plates to glass plates because of their fragile, tactile nature and because “glass has a shorter life than metal,” much like the human life.

While she is dedicated to photographing the living, she also transforms paper or digital images of the dead—like that old-timey couple—into one-of-a-kind physical wet plates. When she gives the wet plate of the deceased person to their family member, she asks that they write a letter to the spirit in the image to begin a conversation with the dead. Kato strongly believes that this physical item helps to bring the spirit of the dead closer to the living by using the photo as a vehicle or vessel for that spirit. She eventually wants to hold a ceremony with the living person in which they burn their letter, hoping the smoke of the message will rise to heaven. “We need to heal from the loss and help others heal,” she says. “But my friend’s death happened 20 years ago, and I’m still thinking about it. I want to heal myself, too.”

Recently, Kato returned to Japan to learn how to make paper. She had learned about a project in World War II in which the Japanese forces fashioned “balloon bombs” out of traditional handmade paper. These balloons carried bombs, triggering devices and other mechanisms across the Pacific Ocean with the hopes of igniting the forests of the Pacific Northwest region of The United States. Kato’s grandparents are World War II survivors, and she felt that learning how to make this traditional paper would not only bring her closer to her familial history, but could be utilized in her creative practice. “I want to use this paper for photographs because I’m printing my identities,” she says. “Making my work more strong.”

“Sometimes the history is hard, but art is much easier.”

Even though she once felt distant from her Japanese culture, going back to Japan and learning traditional paper-making, as well as other skills like shibori dye, candy making and tea ceremonies, brings her closer to her own identity. “Little by little, I’m learning about myself more. I understand more why I do this,” she says, motioning to her equipment.

Kato is currently pursuing her Master of Fine Arts degree in photography at the University of Utah, continuing her work on funeral images and wet plates. She is also beginning to combine photography with printmaking by creating anti-war propaganda posters in Japanese and featuring old photos of children. She hopes that art will find a way to bring awareness to the way war affects youth. “Sometimes the history is hard,” she says. “But art is much easier. Using art and learning how I felt about it has created that connection.”

More on SLUGMag.com:

Another Valley: Granary Art Center

Ushio Shinohara Exhibit Opening @ CUAC 01.18