Trent Nelson: Photographer for the Outsider

Art

When viewing a photographer’s portfolio, you can grasp within the first few seconds what they’re trying to communicate through their photos. However, with Trent Nelson, predictability is not a niche in which he feels comfortable. From his beginning as a photographer for local hardcore shows to being one of the few visual documentarians of the FLDS community, his work is anything but monotonous. Being rooted in the punk and hardcore scene has conditioned him to not take everything at face value and taught him that people with whom he’d never think he would find common ground were actually more relatable than he’d anticipated.

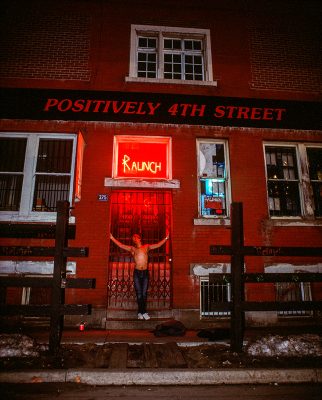

Coming up from the Bay Area, Nelson found his penchant for photography while attending shows at the infamous 924 Gilman St. in Berkley, California, absorbing the styles of photographers like Murray Bowles. In 1988, Nelson moved to SLC and began photographing local delicacies such as Insight, The Stench and Bad Yodelers at The Word, Pompadour, Cinema In Your Face and The Speedway Café. Word of mouth, zines and being one of the only photographers in the scene helped solidify Nelson’s presence.

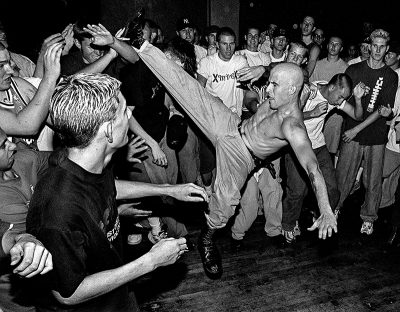

“At Gilman I photographed this Youth of Today show and I got this shot where everything clicked,” Nelson says. “There was this skinhead guy leaping off of the stage, and Ray [Cappo] is right in the center and there’s a guy flying into me from the side.” Nelson made a print of that photo and gave it to the band, which is now on the cover of one of the reissues of Break Down the Walls. “I kind of got known for that photo,” says Nelson, “and then Operation Ivy came around, and I photographed them and I had a cover of Maximum Rocknroll with that photo.” For him, bringing prints to shows was the most intuitable form of advertising his photography, and people started recognizing him as “the guy with the camera.”

“You can go into a show and size up who the dangerous people are and who’s looking for someone to pick on, or who’s going to get picked on.”

“The challenge at punk shows was cameras were manual focus,” says Nelson. “You had to do all the controls, and that meant you had to hold it up to your face and you couldn’t see someone flying at you.” Nelson always had to keep his wits about him when documenting these shows because, not shockingly, they often got violent. “You can go into a show and size up who the dangerous people are and who’s looking for someone to pick on, or who’s going to get picked on,” says Nelson. “That’s the same thing with being a photographer in those environments—where should I be? Who should I watch out for? Who to stay out of the way of. Move in when you need to and move back when you don’t need to be up there.”

While some of Nelson’s photos may have presented Salt Lake’s hardcore scene in its most violent moments, they also capture its vibrancy and intensity that makes it feel so visceral. Since Nelson was one of the only photographers around, his photos share a special connection not only with him but also with the people in the stills. “I have people email me and are like, ‘I’m in a picture you took of me at the Speedway in 1988 stage-diving. Can I get a copy?’” says Nelson, “and I’m like, ‘Oh yeah! That’s going right to you!’ It’s always amazing to see who finds themselves in the pictures. This is without Facebook tagging; this is just people organically finding stuff.”

“There are people doing certain crimes, and they get arrested and charged. But then you find people who are respectful who are in, people who are respectful who aren’t living it, and people who are respectful who are trying to shut it down.”

The photos capture the energy of the time in which they were taken and also showcase a time when punk and hardcore were still underground and dangerous, as opposed to now, where being alternative is the norm. “It’s like Disneyland—there’s little kids; it’s safe; everyone is filming and shooting,” says Nelson, describing the Masked Intruder and The Interrupters show he attended earlier this year. “I was trying to get a good picture with a camera working around all these people, and it was very difficult to get something with that energy.” While the culture that Nelson grew up in was becoming a mainstream accolade, his sense for discovering new subversive groups shifted. “I was working at the Salt Lake Tribune, and one of our other photographers was covering polygamy,” says Nelson. “A year or so went by, and I dove in and started covering the Warren Jeffs group down in Colorado City.”

Though Nelson was warned about the dangers of the polygamist communities and the onslaught of crimes that took place, he simply shrugged it off the same way he did when people called punk rock a derisive subculture of derelicts. “That mentality helped me cut through the fog around these people,” says Nelson. From a formal-journalism stance, he didn’t always agree with them, but his role was simply to tell their story. “There are people doing certain crimes, and they get arrested and charged,” says Nelson, “but then you find people who are respectful who are in, people who are respectful who aren’t living it, and people who are respectful who are trying to shut it down.”

One thing that attracted Nelson to the FLDS community was how a lot of the ethics he picked up from punk rock translated so well in this community. The FLDS community was (and still is) an ostracized and misunderstood subculture, and Nelson approached them with a genuine and equal interest in every member from housewives to prophets.

“We’ve met people who were children when they were in the raid in Texas in 2008 and were taken from their families. Now we’ve met them recently, and they’re out of the group and they look just like regular kids.”

“It was a very difficult gig,” he says. “I went down, and no one wanted their picture taken. They didn’t like me; they wouldn’t talk to me. Gradually, I think they started to come around and understand that I was sincerely interested in who they were.”

Naturally, not everyone was accepting of an outsider, a photographer no less, coming into their world and documenting their lives. “There was a lot of negative vibes directed at me,” recalls Nelson. “I think that, in the end, people will be glad that I was there, documenting even the low points of their lives.”

In the near-15 years of work Nelson has done with the FLDS community, he’s covered court cases and trials, the 2008 raids in Texas, prophets getting arrested, temples being built and taken over, and people losing their land getting evicted from their homes. “By some stroke of luck, I’ve been the one photographer that’s covered most of these huge events for this community,” says Nelson.

Initially, the photos were used to illustrate the daily stories that ran in the Salt Lake Tribune, but Nelson was careful to archive all of his photos on his website, as well as keeping in contact with the majority of the people whose lives he documented. “It is part of a larger body of work, with thousands of pictures of hundreds of people,” says Nelson. “We’ve met people who were children when they were in the raid in Texas in 2008 and were taken from their families. Now we’ve met them recently, and they’re out of the group and they look just like regular kids.”

“A lot of these people who I compete against and work with here in town have been doing it for decades, and what makes [them] great is that consistency.”

The value of Nelson’s photos is underscored by how much he stresses the importance of holding a degree of consistency in his work in the digital world. “I don’t think you can make yourself better than the world on the internet because everyone is posting what you’re doing,” says Nelson. “A lot of these people who I compete against and work with here in town have been doing it for decades, and what makes [them] great is that consistency.”

Another thing that keeps Nelson above water and continually creative is that he doesn’t rely on Facebook or Instagram to house his work, focusing on owning his own platform along with his photos. “When I was in high school, MDC was singing about multi-death corporations, and today, it’s Facebook, Twitter and Instagram,” says Nelson. “I don’t completely avoid them, obviously, but I do have my own site that I control and publish on, and I might not get as much traffic as if I posted stuff on Instagram, but I get the right audience. People find it, eventually, and I’d rather have that integrity.”

If there’s anything for us creatives to take from Trent Nelson, it’s to be in control of how you present yourself. In today’s world, that can mean claiming ownership of your work, securing your own website so people can see it, being consistent in your craft and, above all else, not relying on social media to do any of your legwork. Now, more than ever in today’s digital bath, people need reminders of that human touch that makes great art and helps decide what’s worth preserving in the long run.

More on SLUGMag.com:

The Speedway Project: The History Within the Walls of SLC’s Legendary Underground Venue

Terrance DH