Mine Versus Mind: The Art Criticism of Douglas Crimp

Community

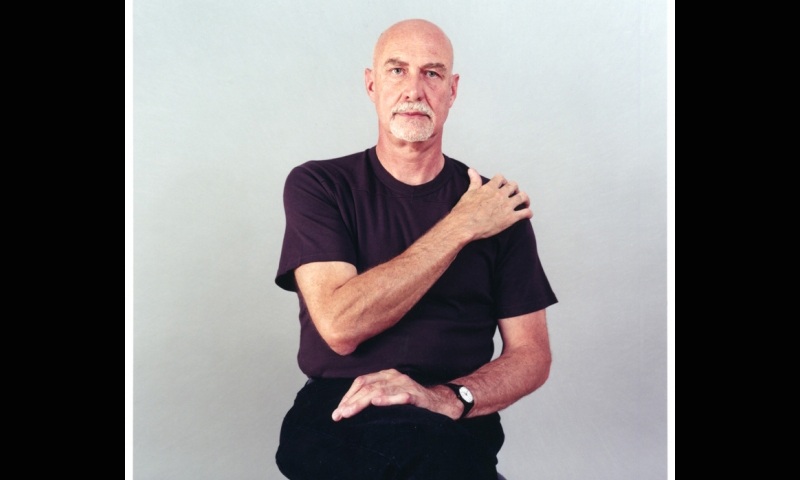

It may very well be that the wall-of-yawn survey courses that drive so many bright students back to retail are “moralizing cultural conservativism disguised as progressive modernism.” This phrase belongs to Douglas Crimp, professor of visual studies at the University of Rochester. Scholars currently debate what this edgy new discipline actually is, but this much is certain; it’s not the same old art-business-as-usual. I spoke with Crimp about his current interests, his involvement in 60s activism and how he broke away from traditional celebratory art history.

The program in which Crimp teaches is the oldest of its kind. It combines conventional art-historical method with sociology, anthropology, media studies and philosophy. Crimp’s essay, The Origin of The Museum and The End of Art, points out a major fork in the road of history in 1830, and insists the museum never had to become the marble temple that we know today. Instead, it might have been an open studio, an interactive and productive space. Crimp’s scholarship explains how worship won out over the workshop. “It still pretty much persists, that division,” Crimp said. So much so that even our own monthly gallery strolls still seem a bit like church.

Crimp does work with the International Museum of Photography and Film, which he describes as an “archive” and “resource.” It shows avant-garde film, classic and popular cinema. It also holds one of the largest film technology collections anywhere. Years back, I went there to admire the cold-war spy cameras made in Latvia by Minox that were used by the KGB. This collection also holds various fossils from the pre-history of photography. “They show [them] in ways that are more interactive and similar to ways a science museum might, or a natural history museum might,” Crimp said.

According to Crimp, artists such as Fred Wilson have been successful at mixing art with natural history. An exhibit of Wilson’s, called Mining the Museum, dealt with issues of race repressed by the venerable institution.

According to Crimp, artists such as Fred Wilson have been successful at mixing art with natural history. An exhibit of Wilson’s, called Mining the Museum, dealt with issues of race repressed by the venerable institution.

Key targets of Crimp’s criticism are the pretentious hymns to the human spirit we see carved above museum entrances. “I try to relate [them] to philosophical aesthetics, to Hegel.” He said. Hegel, you may have learned in a survey course, was the philosophical Napoleon who first thought up universal world history. He was also the white guy that Marx stood on his head. Crimp’s own hope, in line with Marx’s, is to denaturalize this middle-brow view of art. “To say that art is something that human beings have always made and that it has always been recognizable as such, that it was divorced from forms of utility; that notion of art is a completely modern and historical one.” Crimp said.

Crimp is currently writing a book on Warhol. “Right now I am looking at that moment in New York culture of both very radical experimentation in the art world and also very radical experimentation in the gay world,” he said. His book looks at how Warhol’s films were taken out of circulation, so that today almost no one recalls them while enjoying all his pretty pictures. These are films without standard shots and cuts, where mouths don’t match words. Like minimal sculpture and performance art, they drive us to look elsewhere, away from faces. Bringing those films back would disturb our image of the saintly Andy. Suddenly, we get a Warhol who works on the sexual body far more than the mind’s eye.

It seems possible to insist that the fashionableness of “retro” will blunt political projects like Crimp’s. But datedness can also strip art of aura, let it become “artifact” and thus raise fresh questions. “That is what I am reflecting on,” Crimp said, “how the present affects that past and how the past can effect the present, if we mine it properly.” Related to this, today’s giga-pixel culture has caused powerful art scholars to dismiss media studies, saying it only encourages the consumption of image-commodities. To this, Crimp replies, “I am certainly interested in digital culture. I don’t think that by paying attention to it that you necessarily are capitulating to it. You can’t just run away from these forms of culture that make you nervous.”

However, Crimp still believes there are productive forms of cynicism. “Even if it was important to believe you could change the world [in the 60s], I also think there was something a little bit megalomaniacal about that. It was a fantasy.” For Crimp, being aware of your own limitations is the first step toward having any real power at all.