The Boy-Legend: Everett Ruess

Community

From the fading black and white photographs, he doesn’t come across as anything extraordinary. Everett Ruess’ soft, rounded face looks younger than his 20 years. He was still a boy when he smiled into the lens or looked off into the red rock horizon, his trusty burro in tow. But the boyish looks belied the intensity of an artistic soul. And in 1934 when he walked into the desert wilderness near Escalante, Utah and disappeared, he walked his way into legend.

From the fading black and white photographs, he doesn’t come across as anything extraordinary. Everett Ruess’ soft, rounded face looks younger than his 20 years. He was still a boy when he smiled into the lens or looked off into the red rock horizon, his trusty burro in tow. But the boyish looks belied the intensity of an artistic soul. And in 1934 when he walked into the desert wilderness near Escalante, Utah and disappeared, he walked his way into legend.

What happened to the guy? Well, no one knows for sure. Some think he died in the wilderness as he had lived for most of his existence out in the desert, alone, either killed by bandits or by the natural subjects of his art. Others say he concocted the whole thing, making a break for a life free of family bonds.

Plan-B Theatre Company takes a look at the boy-legend with its latest production and world premiere of The End of the Horizon. Written by Utah playwright, Debora Threedy and directed by Kay Shean, it’s a fictionalized account examining Ruess’ relationship with his family and his parents’ attempts to search for him right after his disappearance. “Like him, I feel a deep connection to the Canyon country,” says first-time playwright Threedy. “So it was inevitable that I’d be hooked by his story.”

That story—not to mention Ruess’ cryptic last-etching found in a cave that read “Nemo 1934″— has inspired researchers, historians and fans to produce countless books, documentary films and even a nod in Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild. Not bad for the short artistic life of a 20-year old.

In fact, you could say that Ruess was the O.G. of the American artistic vagabond. In a way he’s the Elvis and Billy the Kid for the artistic souls who have ever been stirred by the sight of red rock monoliths or infinite sky. Ruess was the young rogue who shook things up with his vision of the world and how he wanted to experience it.

By the time he disappeared he had soaked up San Francisco’s culture, tracked down his favorite artists of the day like Maynard Dixon and Dorothea Lange to learn all that he could. Then, there’s his intense connection to the environment that strikes a chord with many in Zion.

The local interest is a given. The cast recently took a road trip down to Torrey and Escalante, which holds an annual arts festival that was formerly called “Everett Ruess Days.” But Threedy’s script caters to more than a Utah audience. Plan-B’s Producing Director Jerry Rapier gives Threedy credit for creating something that doesn’t resonate solely with individuals who enjoy trips to Lake Powell and a heaping serving of funeral potatoes.

“Regional stories are important and Debora’s script as a first-time playwright would stand up against anyone else’s tackling this story,” he says. “Ultimately, though Horizon is about a family and their attempts at communicating with each other.”

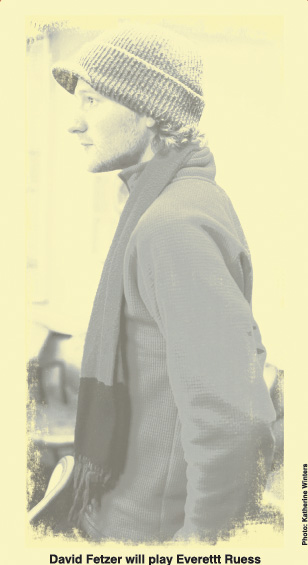

Threedy’s script focuses on Ruess’ parents—god-fearing, middle-class Southern Californians who wanted a stable life for their two sons. Though the prodigal one, Waldo, is a poster child for obedience, it’s Everett that takes over the psyche of their mother Stella. Threedy does double duty, playing the well-intentioned, but overbearing mother. David Fetzer, a local musician and frontman for the band Mushman, walks in Everett Ruess’ shoes during flashback scenes and haunting dream sequences in the play.

Through an extensive collection of letters and his art work, Threedy knew Ruess’ short life was rife with detail and speculation about his sexuality, the true nature of his relationship with his family and his desire to turn his back on civilization. After a remarkably quick first draft and some refinement at the Utah Shakespearean Festival’s New American Playwright workshop, Threedy’s script is mercifully svelte, stripping the story down to its barest emotional bones, as stark as the landscape of the remote red rock country.

The set design by Randy Rasmussen riffs off of Ruess’ famous woodcut prints. The black and white figures are at once familiar and haunting, giving the cast a minimal backop against which to paint their environment with the obligatory dysfunction and miscommunication rife in every family unit.

Threedy provides no literal ending for the audience, just a certain amount of closure for a restless Stella Ruess. Fact fingers and myth busters won’t find any closure here, but the mystery and the unanswered questions of his life and disappearance make up so much of Everett Ruess’ appeal.

“A lot of people are drawn to Everett Ruess’ career and story because they were so short,” Rapier says. “It’s the tragedy of an artist struggling with his family, with himself and finding finally a niche and then having it all end.”

The End of the Horizon will be shown from March 14-30 in the Studio Theater at Rose Wagner, purchase tickets online or call 355-ARTS. Many other events will be occurring in conjunction with the production.

Ken Sander’s Rare Books will host “Everett Ruess Found! Two Weeks Only” which will feature many original artifacts and artwork from Ruess’s short life. The exhibit will hang from March 17-30. A special free screening of Diane Orr’s Lost Forever: Everett Ruess, will also be held at Tower Theater on Tuesday, March 18 at 7 p.m. in conjunction with the play.