Gnome Two Ways About It: Lawn Gnomes 2020

Art

When March came along and the world changed, so did the traditional opportunities for public art. Enclosed gallery spaces suddenly became a potential public health hazard, and the notion of gathering for a new exhibition became especially fraught. Since then, the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) has been looking for ways to connect people to tangible things, says Executive Director Laura Hurtado. Enter Lawn Gnomes 2020, a growing exhibition of art installations that lives on the front lawns of artists.

The title of the exhibition is a bit of a misnomer, if you will—none of the 11 currently participating artists have actually installed garden gnomes. Instead, think of these as public sculptures. The name comes from a 2011 UMOCA exhibition, Lawn Gnomes: Eat Your Hearts Out. In that exhibition, Visiting Curator Micol Hebron organized the event under the idea that the public ought to have a chance to participate in communal art. “The front lawn is a private plot of land that is publicly visible and functions in urban and suburban society as an important signifier of taste, individualism and community,” said Hebron in 2011. “Lawns are a teeny slice of utopia: They can proclaim your political position, your ecological philosophy, your domestic ideal!” Lawn Gnomes works as a spiritual successor to that pitch, which may be stronger now than it was then: Let’s open our sense of property up to the idea that others may enjoy what we privately own.

Lawn culture is particularly pronounced in Utah cities built for transportation by car more than walking

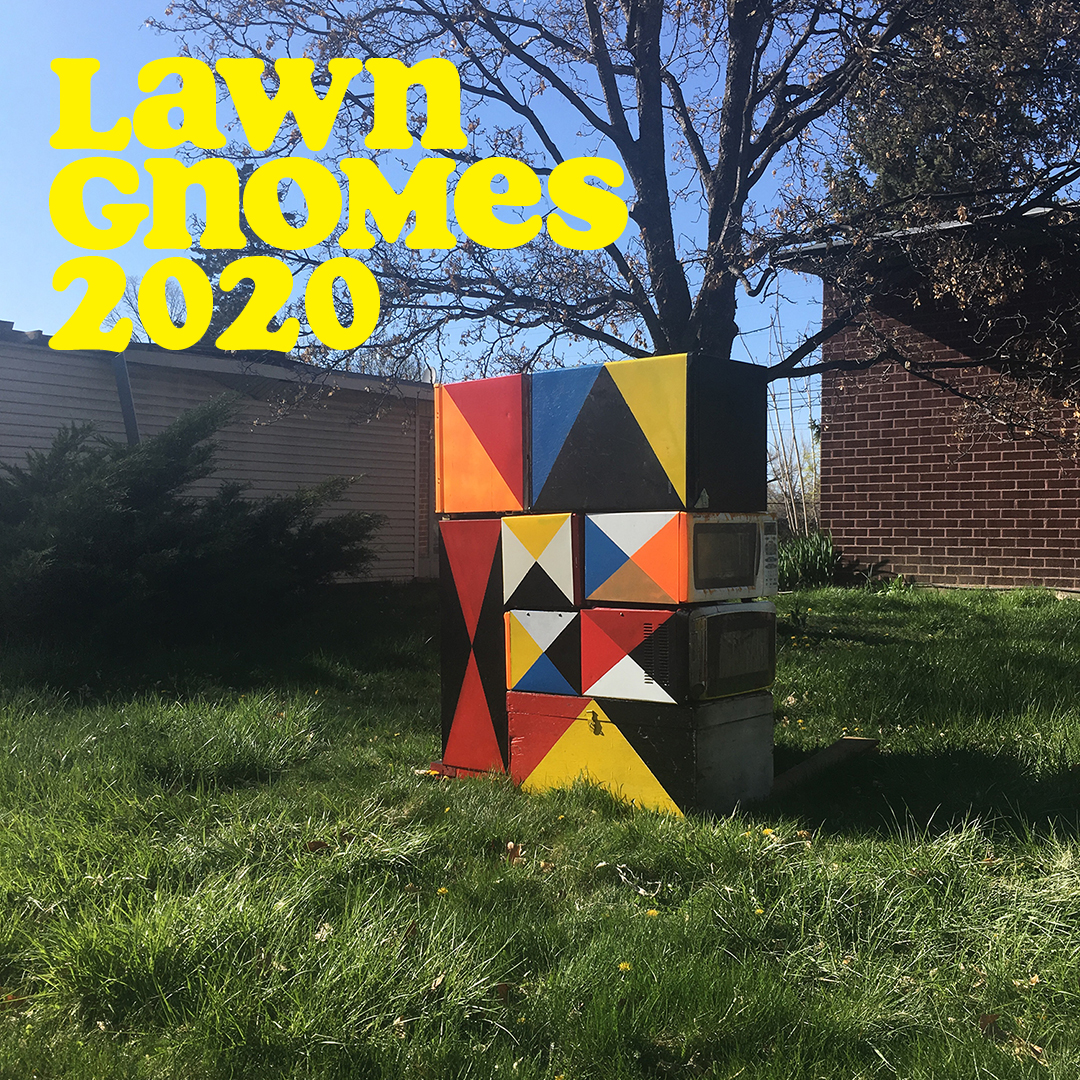

For instance, Jared Lindsay Clark’s contribution uses old boxy home appliances and items—mini-fridges, microwaves and trunks—as building blocks for a colorful sculpture. There’s a sense of usefulness gleaned from the decrepit objects that make a home, of making use of the resources we might otherwise toss out. From one angle, it’s trash on a lawn; from another, it’s a mural. Clark’s sculpture reminds us of the way art makes use of materials we take for granted, even during times of abundance. During COVID-19, that revitalization is only more pronounced.

Lawn culture is particularly pronounced in Utah cities built for transportation by car more than walking. Our suburbs are sprawling and separated by wide streets, and in this moment, it serves us: Manicured gardens of grass and xeriscaping are gallery spaces of their own, but the goal of Lawn Gnomes 2020 is to break down the intentional sense of boundaries and isolation that private property tends to reinforce. “Isolation was such a strong feeling in the beginning of quarantine for those who had the privilege of sheltering in place,” says Hurtado. “In the beginning, we asked ourselves as a staff what we could do to continue to serve our audiences and the community at large. We felt like people were looking for—beyond safety and health—a sense of normalcy, comfort, connection, community and something to do.”

The rapid onset of telecommunications reliance in 2020 has somewhat fatigued us against it. UMOCA Curator Jared Steffensen was tired of Zoom meetings and interfacing with screens. He felt that such an approach would only reinforce isolation. It was his idea to revive Lawn Gnomes for a new decade. “The main idea is to think outside of the gallery walls,” says Hurtado, “[to] expand the role of the artist, and to call upon everyone in the community to innovate and reimagine lawns as both private and public spaces. While we stay home, stay safe and social distance, we can still continue to create and to think about new ways to engage [with] our city and our neighbors.”

“It’s meaningful to see so many artists take on the project and make work.”

While the exhibition currently has 11 participating artists, it’s ongoing, and the museum invites anyone who desires to participate. Patrons can contact the curation team at lawngnomes@utahmoca.org for a yard sign designating them as a gallery space and opt to share their address on the growing list of sites that museum-goers can access to see installations in person. “To date, the project has spread from Toole to Ephraim,” says Hurtado. “It’s meaningful to see so many artists take on the project and make work.”

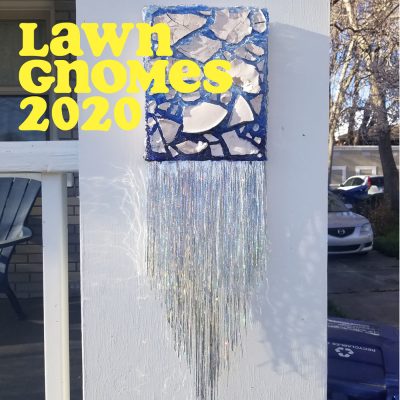

The body of work is already diverse. Ruel Brown’s work is a swirl of white lines on a black background, bending and curving like a zebra floral with the letters of the word “acceptance” stacked on each other. Cara Krebs used her canvas to affix a spill of iridescent streamers to what looks like broken porcelain. Jared Steffensen’s features a circular rack of mixed-media images, inviting the viewer to walk around the installation.

One of the more striking installations is Colin Bradford’s, which sits on his porch at night: A white neon sign oscillates between reading “FEAR”and “FEEDS,” looping into “FEAR FEEDS FEAR FEEDS,” ad infinitum. This was made long before the pandemic. “I saw a feedback loop of fear feeding more fear in our culture around lots of issues,” says Bradford. “Fear during the COVID-19 pandemic has motivated everything from toilet paper hoarding to brutal hate crimes against Asian Americans.” It’s one of the more heavy-handed installations for sure, but not so overt as to lose its edge. “Let’s find it in us to respond with love and empathy rather than fear as we reduce everybody’s risk by working together (apart) to

prevent the virus’ spread.”

Visit the exhibition online or email lawngnomes@utahmoca.org for more information on the exhibit, to obtain an official map of currently participating artists or to join the project yourself.