Rire-Woodbury Dance Company: Surfaces

Art

The Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company wrapped up their 2008-2009 season last weekend with three performances of Surfaces. The show, which spotlights the work of three accomplished choreographers, begins with a collective improvisation featuring distinguished alumni whose tenure with the company span its 45 year history. The spectacle of mixed ages and styles of expression displayed by the various dancers drew warm applause and cheers from the opening-night audience. Clearly, Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company has assembled a dedicated following over the years as enthusiastic and committed to the lively arts as are the members of company.

The first choreographed work of the evening was a restaging of “Strict Love,” a piece written by Doug Varone in 1994. This dance is set to music culled from a radio broadcast of pop hits from the 70s, in particular the music of The Jackson Five. Prominently featured is the vacuous between-song banter of a network DJ. Meanwhile, the members of the dance company, dressed in drab grays to resemble Maoist workers or Buddhist monks, rehearsed a number of highly ritualistic moves, not so much expressive as indicative of a “philosophy of no mind.” The result offers a contrast of two highly distinct forms of soul, each superficial in its own way.

The next piece was a new work commissioned by award-winning New York choreographer Susan Marshall. The show program announces Marshall is the “recipient of three ‘Bessies’ and the MacArthur ‘Genius’ Award, she is the Artistic Director for Susan Marshall & Company and has created works for the Frankfurt Ballet and the Lyon Opera Ballet.” None of this information would come as a surprise to an unwitting member of the audience.

The suite of loosely related dances showed a broad range of moods and movements (from grave to playfully erotic to deliciously perverse), and displayed an especially inventive use of simple but unexpected props, many of which achieved rather startling effect. Just one which comes to mind is a paper napkin, which one of the dancers blows into the air, allowing the other to catch in it mid flight. Easily produced, this simple stunt nevertheless created the visual effect of a film run in reverse, with the result of an eerie uncanny aura enveloping all other movements within the dance.

The choreography in each of these dances, which called for a number of difficult and scarcely supported aerial movements, brought forth an impressive degree of grace and athleticism from the performers. A sense of high-purpose devoid of any identifiable purpose pervaded each of these pieces. In other words, here the audience was privileged to behold movement as an end unto itself. Marshall’s choreography offers a perfect example of why modern dance is not simply great entertainment but indeed genuine art.

Charlotte Boye-Christensen‘s “Degrees of Separation,” the last piece on the evening, provided a drastic complement to the first half of the program. Employing the music of famed minimalist composer Steve Reich, this piece provided the audience which a far more ensemble or choral effect. Reich’s “Different Trains,” to which the dance was set, is a brief epic whose initial rhythms and tones have been cloned from recording of Amtrak trains and the voices of railway workers.

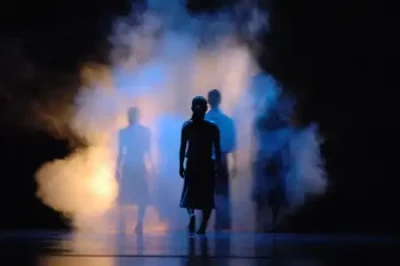

The effect is a feeling at once energetic and nostalgic. The hustle and bustle of commuters and tourists is evoked by the hasty and somewhat robotic movements of the troupe. The initial mood incrementally darkens however as the sound of whistles turn to air-raid sirens. The dancers dark blue costumes, initially reminiscent of business attire, begin disturbingly to recall the uniforms of prisoners of war. The energetic pacing soon suggests the cadences of a forced march onto trains which will speed toward concentration camps.

The finale of Boye-Christensen’s “Degrees of Separation” concluded the program on an uncomfortable note for me, though this owed much to my prior familiarity with the music. This rather dark tone seemed however to have been lost of a large portion of the audience, which most likely was not acquainted with either Reich or his “Different Trains,” whose theme could hardly be considered superficial.