These Little Hands: The Craft of Lindsay Heath

Music Interviews

I remember seeing Heath onstage with Redd Tape in the nought years of this millennium. I also saw her play synthesizer in one of the most harmonically interesting and criminally forgotten Salt Lake bands, Delicatto. “I couldn’t drum in that one,” Heath tells me, “because I had broken my arm skateboarding.” Additionally, Heath contributed drums to the earliest incarnations of Vile Blue Shades. Onstage, she was consistently a startling presence. A precocious and ferocious musician, she was a visual freak flag. All this musical Kid Madusa (one of her stage names) seemed to want for was a smelted boomerang and a pouch of human fingers. While it may be tempting to approach such strangers, one rarely does so with impunity. I was brazen enough to step into Heath’s ambit a few days after seeing one of her performances. As I recall, our conversation went every which way but forward. Still, it did initiate between us an acquaintanceship that lasted a couple of calendar years. Though I never could say exactly when, at some point I found I had won Heath’s trust.

My ongoing friendship with Heath has allowed me to follow her musical fortunes and take a keen interest in the various twists and turns, and ups and downs of her artistic trail. However, my relationship to Heath took a very unexpected turn when she asked me—at the same time this article was being planned—to play guitar in her latest project, which will play a series of CD-release shows in August. To take part in such events was an opportunity for which a fan like me could only vaguely hope, because, as Heath insists, “Finding the right accompanists is one of my very biggest challenges. Everything has to feel right.” Somehow, I got the call. Lindsay Heath’s current lineup includes Cache Tolman on bass, Skyler Arbon, Michael Sasich on guitar, Jaime Hunt on violin, Klaus OrNot on cello, Camilo Torres on drums and yours truly on guitar.

Though most readers will know Heath first as a drummer and only next as a keyboard player and singer, her first instrument was, in fact, the guitar. “I begged for a guitar,” she says, “and got one for Christmas when I was 6 years old.” It is hard to imagine Heath submitting herself to a teacher of any sort, and so it comes as no surprise that she is entirely self-taught. “No one showed me even how to tune the thing, so I stumbled into drop-D minor, which turned out to be standard tuning for the ‘90s. It was the Nirvana thing.”

For each new generation of musicians, there will be a band among bands that defines and embodies the era—what it is—and that issues a musical call to arms to all who have ears—Sons of Scotland, will you fight?! In my case, I was all but physically marked by my first encounter with Led Zeppelin. It was the hammer I never saw. Like so many songwriters of her generation, Heath’s discovery of Nirvana was her holy WTF moment. “It was not of this world,” Heath tells me. This fact might not have been noteworthy once upon a time, but in the present electronic dance hegemony, it has become genuinely possible to step into a room full of kids from Generation Whatever and find that not one of them has heard the name Kurt Cobain—astonishing, but true. Yet, to see Heath recall the urgent feeling of that moment brings to mind the words of the British poet William Wordsworth—“Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, But to be young was very heaven!” Upon such feeling, more than one great artist has founded a career. From Nirvana, Heath found her vocation.

In particular, Heath and I discussed our fascination with Annie Clark (aka St. Vincent), who took part in the recent Nirvana reunion. In interviews, Clark has mentioned the lasting impact that the band had on her. I found it remarkable that the same band could so profoundly influence two artists with such different musical backgrounds. Clark, who possesses impeccable form, studied guitar under the tutelage of a world-class jazz musician (her uncle, Tuck Andress). Meanwhile, Heath developed her sound entirely without instruction. One wouldn’t know this upon listening to the new CD, Holy Medicine. “I kept the songs stripped way down,” Heath says, “so that the live performance would sound true to the original compositions.”

Unencumbered by any tawdry sonic bling, each song on Heath’s album is free to drift effortlessly in and out of safe and perilous shoals of melody and harmony. “They are all the result of fumbling around,” Heath insists. Mere flukes or not, many of the tracks evoke legendary bands, while nudging their signature sounds—as an art instructor might—toward possibilities even the very best, at times, lacked the skills or guts to achieve. It is easy enough to hear echoes of Pink Floyd in the nebbed-out vastness of “Crawlspace.” Rather than merely imitating a classic tune such as “Breath,” Heath modulates the chord progressions and warps the melody in ways that recall the untethered and reeling piano and violin concertos of Sergei Prokofiev. Far from simply imitating the masters, Heath comes wonderfully close to mastering them back.

Heath’s prodigious capacity to hear, mimic and alter melodies isn’t revealed in its bizarre fullness until she grabs her guitar to show you the actual process through which her songs come about. I sat with Lindsay in her living room as she lifted a becrudded old Ovation that might once have been pawned for beer money. I sat, stunned, as she proceeded to hook her thumb over the top of the neck, not grabbing only the fattest string like a gifted slacker (for instance, Jeff Beck), but rather thumbing an entire barre chord while somehow freeing a finger to engage the thinner strings from underneath. From my own woefully over-cultivated perspective, it was like watching someone eat a rice bowl with scissors. Sure, dood, it works, but come on! And yet, the results were undeniable. In response to my bewilderment, Lindsay announced, “Yeah, these little hands did all that.” Seeing this brought to mind YouTube videos gone viral. These showed amateur musicians from undisclosed regions of the undeveloped world, drawing astounding sounds out of North American musical-instrument detritus. This they did using calloused knuckles, prehensile toes or discarded flashlight batteries. The cunning methods these nameless everyday geniuses had devised while working with cast-off gear was not unlike the way they handled songs, salvaging scrap and reworking parts into wacky, new combinations that worked as if by magic. I began to see in Heath a sort of musical bricoleur, thrifting and matching on the fly, though “I am not a shopper,” Heath says. “I went to Decades today and was exhausted immediately.”

Heath applies this same rescue-and-redirect method to shaping her own materials. “I throw away a lot,” she tells me, “though I hold on to more than I trash.” Her songs never emerge all at once, but slowly take shape over the course of continuous revisions. “I will work a song to death until it gets born again as something else.” Knowing many of the prevalent myths about the creative process, I asked Heath if songwriting is easier or harder than it looks. “Really, it’s both,” she says. “I have to work at it all the time, and I hate myself when I don’t do it. But it can never be forced.” I asked her if creativity, in the final analysis, comes down to skill or luck. She says, “I guess I’m just skilled at being lucky.”

Another important aspect of Heath’s music is her knack for producing unexpectedly convincing lyrics. Heath admits that aside from the standard angsty fare—Sylvia Plath—she does not read much poetry, but she is always searching for poetry in the songs of others. It’s not always easy to find. We share a laugh at the expense of some of our favorite bands. “Their words are so stupid!” she says. I could not disagree. Heath says her songs are meant to tell stories, and it’s important for her that the listener captures that. Her songs, she says, are like bandages wrapped over life, wounds you can’t see, but come to know by what seeps through. “I don’t think you ever heal from some things,” she says. “But you can get better at bandaging.”

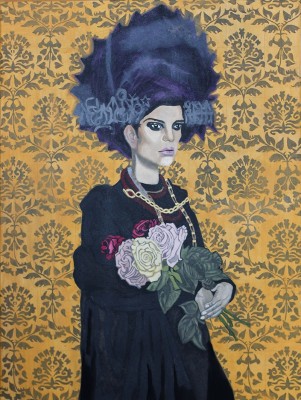

At times life has become difficult enough that Heath felt unable to perform. As with many artists, depression has been both an inspiration and an obstacle. The CD-release shows scheduled for August will mark the end of a performing hiatus of several years. In fact, Heath chose to let a year separate recording her songs and bringing them to the stage. “When it comes to playing them, I feel these songs deserve justice.” Deserve justice—that is a favorite phrase of Heath’s. “I was not willing to rush anything for the sake of meeting a deadline.” An important part of emerging from depression has been Heath’s return to visual art. “I’ve always loved painting, but I became disheartened when all my work and supplies were stolen in 2006. When her recording was finally finished, Heath had time to buy new supplies and awaken her passion for painting again. “The whole time I was making music, I was also spinning visual concepts in my head.” The clearest evidence of Heath’s connection of art and music is her song “Painted Queens,” which catalyzed the series of canvases now beginning to cover the walls of her house.

Odd as it may seem to find Lindsay Heath practicing the craft of home decorating, this appears to be the latest stage in her personal journey—settling down. While Heath has found assistance from many sources, a most significant champion of her work has been her partner, D’ana Baptiste. Though it may have been strange for this quondam feral creature to take up a permanent residence and the responsibilities that come with it—“including kids,” Heath says—this setup has given her a secure position within which to return to her creative life with a sense of security and full confidence. “D’ana has been one-hundred-percent supportive of my project,” Lindsay says. It’s in a beloved book by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry that a wild fox tells a wee prince, “I cannot play with you; I am not yet tamed.” Then the fox asks to be domesticated. This he defines as establishing ties that make each partner to the other unique among all things. Nothing visible changes, and yet the reciprocal choice recreates the whole world for both parties. It’s a world for Lindsay Heath—one I encourage SLUG readers to explore through her new CD, Holy Medicine.

Lindsay Heath Orchestra will be performing three local shows in the month of August. Catch this action Aug. 1 at Shred Shed, Aug. 2 at Urban Lounge, or headlining at the Craft Lake City DIY Festival on Saturday, Aug. 9 on the Gallivan Center’s Main Stage.