LGBTQ+

Chelsea Wolfe

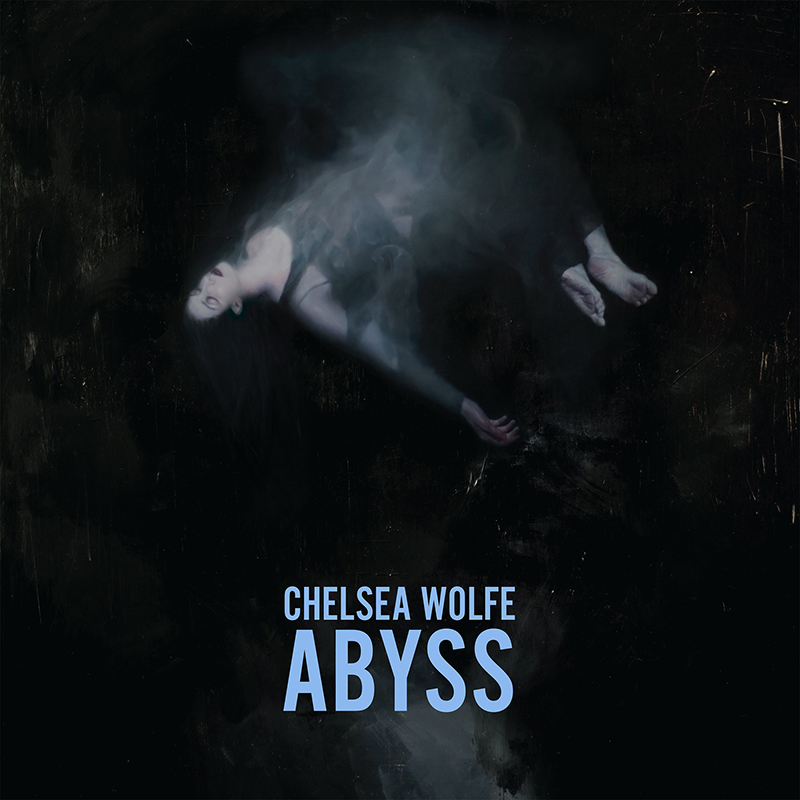

Abyss

Sargent House

Street: 08.07

Chelsea Wolfe = (Björk√Joan Baez) / GodfleshSleep

Two years after her breakout album, Pain is Beauty, Chelsea Wolfe has again commanded a confluence of genres to synergize into a new, consuming ebb. It’s rare for an artist in the realm of popular music to generate a fine-art feel for her work as Wolfe does with this record, and in general; though Abyss avoids any unnecessary sonic noodling, instead favoring a narrative that bellies concavely, much like an REM-afflicted sleep cycle. In Abyss, she maintains her penchant for wending her gorgeous voice through the often ugly or strident aural lattices of metal sub-genres and industrial music. Abyss proves to be her most cohesive album yet, as she’s transcended this instrumental conceit using a process similar to that which she employed on Pain is Beauty.

I, too, have experienced sleep paralysis, Wolfe’s principal lyrical motif in Abyss. The anti-arc of the album indeed mimics the tumult of this tarnished sleep cycle. The queer buzzes of demonic speech that antagonize in the limbo between slumber and waking life crackle in opener “Carrion Flowers” with ominous bass, and they slam with hard-hitting kicks to the chest—and Wolfe breathes in her thorny-rose croon atop industrial-style machine-gun drum fire. The sludge of “Iron Moon” cannonballs into paralytic caverns and becomes “Dragged Out” through an inward somnambulism.

With less percussion, “Maw” arpeggiates toward the tom-y “Grey Days,” whose juxtaposing, tense drumbeat rhythm punctuates Wolfe’s question: “How many years have I been sleeping?” The corporeal drumming yanks at our consciousness toward the netherworld side of the River Styx. “No hunger, no fever, no loss, no wager / Could wake your mind,” Wolfe continues, lapsing more into her sonorous, dreamlike singing. “After the Fall” operates as a dirge ridden with corrosive blips, tonally high and low with bit-crushed percussion. Therein, Wolfe mingles cryptic, personal-seeming lyrics with images that are symptomatic of sleep paralysis: “Chasing the sun / I can’t wake up / Scream and run / Don’t let them win,” whose accompanying fuzzed-out bass melody again evokes the voice of the condition’s “intruder,” as it’s known.

“Crazy Love” wallows as Abyss’ acoustic, Unknown Rooms–esque nadir and suggests that, with less going on, Wolfe’s anxious psycholinguistics come to the fore to invoke emotional desolation. The devil enters through Wolfe’s sepulchral heart: “Crazy love, it’s not you I fear / You let the devil in / You hold him near,” Wolfe sings in this, Abyss’ most lyrically simple track. Its songwriting evinces the unrest we feel while dreaming and combatting our immobile state amid nightmares—ironically, in the thick of the album, it’s Abyss’ most lucid song.

“Simple Death” reawakens the record, but begrudgingly so. It stirs and wriggles with more despondent lyrical declarations of awake-apneic struggle. Wolfe sings demurely of our “Dark, dark world / Dangerous religion,” vaguely addressing troublesome cultural phenomena—albeit just saliently enough to illustrate that our sleeping internal dialogue sifts sociological plight through the lens of our own, respective melodramas. “All the sinners and the saints,” Wolfe sings in “Survive,” “Move in the same direction / They walk in place / Until the end.” This stanza, for me, operates as the lynchpin of the record in my favorite song on Abyss. Wolfe sings gestures mimetic of unsuccessful bodily lurches to rise—a stunted Icarus—and visceral tom strikes bat the listener down.

Penultimate track “Color of Blood” channels “Electric Funeral” as the track oozes more fuzzy bass. Wolfe sings with a lisp via a vocal effect—“A hunger never satisfied / I can’t keep you off my mind,” she says of a lover. “… I held you at a distance then / So I could keep you sacred now.” Wolfe’s reconstruction of herself in this work bares her most vulnerable self before the oncoming musical barrage of percussion in “Color of Blood.” Although sleep paralysis shapes the character of the album, Wolfe uses it mostly as a vessel to discuss relatable, recurring demons of the human psyche that affront us in these impotent states. Our minds project the intruder we detect in Wolfe’s instrumentation.

Album closer “The Abyss” limps awake from the terror in our consciousness, but “When I move it pulls me closer,” says Wolfe. “When I swim it drags me under / When I dream it steals my wonder / Set me free from my slumber.” Awkward, dissonant piano twinkles underscore the abyss that Wolfe bespeaks, who hopes to “Stare it down, the abyss / Run away, run away from it.” The ending of Abyss suggests the will to push past the convoluted suspension in this chasm, but we’re cut off from that turning point.

Album closer “The Abyss” limps awake from the terror in our consciousness, but “When I move it pulls me closer,” says Wolfe. “When I swim it drags me under / When I dream it steals my wonder / Set me free from my slumber.” Awkward, dissonant piano twinkles underscore the abyss that Wolfe bespeaks, who hopes to “Stare it down, the abyss / Run away, run away from it.” The ending of Abyss suggests the will to push past the convoluted suspension in this chasm, but we’re cut off from that turning point.

Wolfe upholds the dreary ethos of oeuvre and has grown all the while. Ultimately, it’s a record that points back into its Abyss, which augments its trajectory strangely and delightfully. Because of this—and simply because it’s fun and interesting to listen to—Abyss is a record that you’ll leave on an unending revolution on your turntable.